How do you get a quality technical translation?

When people hear that you work as a translator, the default assumption—once they understand that you work with the written word, not spoken language—is that your days are filled with literature and poetry, or maybe subtitles for a film or TV series. But creative works are only a tiny sliver of the texts that are translated around the world every day; the vast majority of them serve practical purposes as documentation, instructions, records, and more in a variety of areas and fields.

Technical translations are one example. Just as technical writing is an entirely different beast than creative writing, technical translations have different goals, audiences, challenges, and concerns than their literary counterparts. Most of us have had first-hand experience with poor technical translations, such as in manuals for budget consumer electronics that can be kindly described as “translated from the Martian,” but we have also encountered countless technical translations that we may not have even recognized as being translations at all.

In the blog post that follows, we chat with Melanie Williams, one of the expert translators in our Cologne office, about the challenges that come with translating technical texts and some strategies for making those translations successful.

“Technical translation” is a broad term

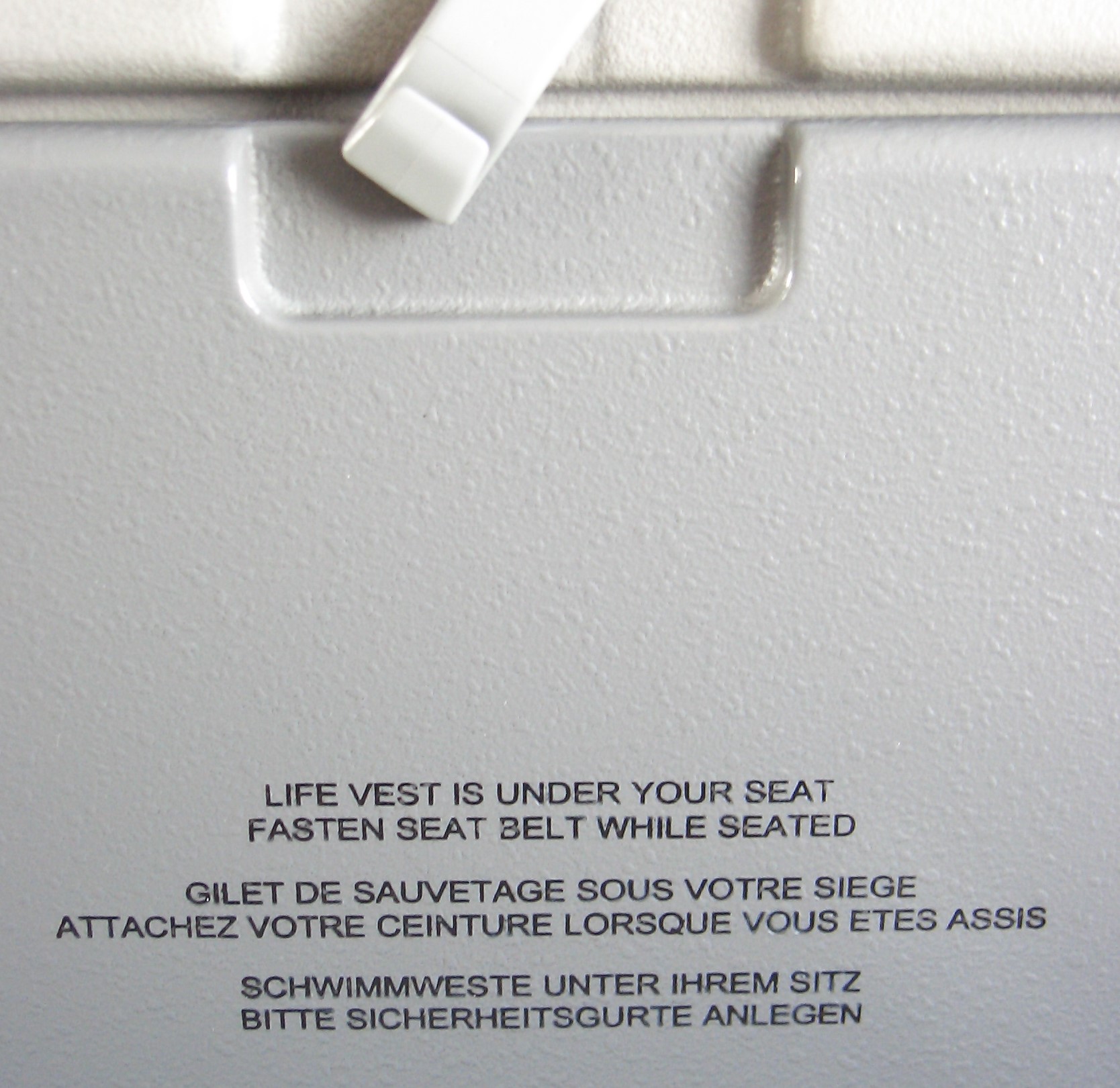

Texts that are considered technical range from patents for medications and user manuals for machinery and devices to software and on-site health and safety documentation in production facilities. All these serve specific functions and come with their own vocabularies. Because these texts use highly specialized terminology and cover complex subject matter, translators working with them concentrate on a few subject areas so that they can fully understand the source material and its context and then express the meaning of it in the target language.

Our technical translator Melanie works mostly with pharmaceutical industry texts, such as testing specifications, analytical procedures, standard operating procedures, and so on, that require her to have in-depth knowledge about the procedures and tests being described, the materials and devices being used, and how all of these things come together. For this Melanie can draw upon years of experience in the area, which she supplements with excellent research.

Technical translators are tenacious researchers who love to learn and collect information

Ideally, a technical translator will have a strong background in the subject matter of any document they are going to translate, whether acquired through study or training, from working in a particular industry, or from having translated similar documents over an extended period of time. Combined with such a background, technical translators use top-notch research skills when they need to confirm that they are on the right path with a translation.

Asking the client for reference material is obviously the first stop, but translators will often turn to the internet if this approach does not yield any results. It doesn’t just end there, though. Most translators and agencies have archives bursting with documentation and reference materials, translation memories and glossaries replete with specialized terminology, and of course, access to the best resource of all, other translators and experts. GLS, for example, has a massive document archive of previous translations; a collection of (electronic) reference materials that includes books, manuals, dictionaries, and policies; and enormous translation memories and glossaries, which are constantly being updated by our in-house terminology team. GLS translators and editors in both offices take advantage of every opportunity to exchange information with each other and get help with hard-to-parse concepts and phrases from native speakers.

Other useful technical translator traits that Melanie highlights are endless curiosity and the tenacity to find that textual nugget that will make the translation sound like it was written by a technician in the lab or an engineer at a drafting table. Interest in the topic of the text you are translating is also paramount, as is having a knack for your usual “left-brained” topics: math, chemistry, physics, engineering, and so on. And as always, practice makes the Meister.

Accuracy and understandability are the hallmarks of a good technical translation

Technical translations, Melanie stresses, need to be accurate and understandable above all else, something which hinges upon the translator knowing the whole story behind the text they are translating. Particularly challenging is the proper identification of such things as machine parts, tools, instruments, devices, etc., especially when one language has more specific nomenclature than the other for objects that look similar. Take the German word Pinzette, which could potentially be translated into English as tweezers or forceps depending on the context. Both are tools used to grip objects, but the correct translation boils down to what the tool is being used for. The same goes for the translation of the German the word Prüfpunkt, which can mean item in a list, test parameter, or even just test.

Other challenges can stem from differences between the default writing styles of two languages. Consider the German Nominalstil, which relies heavily on the construction of lengthy noun phrases, versus the tendency of English to rely on verbs. Or perhaps the pervasiveness of passive voice in German standard operating procedures (SOPs) versus the English preference for active voice in these documents. When you combine these with the fact that most technical documents are not written for translators by specialist technical writers but instead by engineers, chemists, physicists, or safety personnel for their own, in-house colleagues (with a healthy dollop of jargon), it can result in source texts with scant context and low readability, even for native speakers of the source text language. All of this leaves the translator with a daunting gap to bridge, but awareness of potential linguistic sticking points can help linguists zero in on trouble areas and devise better solutions relatively quickly.

Despite all of the challenges encountered when translating a technical text (which, Melanie notes, are similar in principle to what a translator might encounter when translating other types of texts), the formatting and textual structure of technical documents can help make translating them easier. For example, technical documents that are submitted to regulatory agencies typically employ a similar type of language, and the information is organized under headings in a consistent and identifiable way. The streamlined and consistent formatting of the documents allows auditors to focus more on the content than on figuring out where to find the information they are looking for. The same applies to translators, who take particular care to incorporate established wording and reflect the formatting of the source document in their translations so that when auditors are comparing the source and target language documents side by side, they can easily see what they are reading.

Flexibility within the structure can make for better readability

All of that may make it sound like technical translations are rigid and devoid of any kind of interpretation in comparison to the translation of other types of texts. Not so, Melanie points out. In the end, the translator’s job is to make the translated text readable so it is useful for the intended target audience. Key there, obviously, is to know who you are writing for and what the translation will be used for. It also means that a technical translator needs to be able to detach from the grammatical structure of the source language whenever necessary and put themselves in the shoes of whoever might read the translation. Individual terms may thus sometimes need to be translated differently than usual in order to accommodate the particular context.

In sum, although technical translation is often viewed as a monolithic category, it is actually a compendium of very specialized subject areas. Translating technical documents involves high-level research (and persistence), great specialist knowledge, a sound background in the grammar and writing styles of multiple languages, and the ability to pay attention to and replicate the formatting of a source text document. It also requires a high degree of textual creativity and the ability to identify context, two factors which are crucial in making sure a translation is readable. When you have a technical document that needs to be translated, be it for a regulatory agency, internal use, or even just for informational purposes, making sure you use qualified, appropriately experienced linguists is essential to ensure that your translation is accurate, and most importantly, useful (and therefore good).

Read more about our approach to translation in these articles.

April 20, 2022 |